Excerpt from 'The Shanghai Gesture'

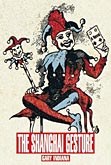

THE SHANGHAI GESTURE

a novel

By GARY INDIANA

TWO DOLLAR RADIO

Copyright © 2009 Gary IndianaAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-9820151-0-0

Chapter One

Among Those That Know, a cabal our story will elucidate in the fullness of time, rumors fluttered that Dr. Obregon Petrie defied the laws of gravity when it suited his caprice.

Reports of Petrie in languorous flight through the velvet-shrouded parlors of his monstrous Victorian folly, of static levitation, even tales of Petrie clinging spiderlike to the plaster grape-and-putti moldings that lined the ornate ceilings of those musty rooms, suffocated by curio cabinets and incunabula, were rife not only in the hushed confabulations of Those That Know, but a topic of idle gossip among the raucous sailors, coney-catchers, fishwives, and floozies who trolled Gin Lane and its tributary alleys at Land's End. These were the human tidewash of any seafaring backwater, for whom no superstition is too far-fetched, and no inebriated fantasy fails to inspire lurid embellishment.

Petrie, airborne or otherwise, enjoyed much esteem at Land's End, for the storm-ravaged shipping town's human debris experienced no end of bleeding piles, recurrent malaria, scurvy, dropsy, high blood pressure, and a lowering effulgence of hardy pox, to say nothing of the port's relentless pestilence of insomnia, a veritable miasmic funk endemic to the area since the wreckage, a century earlier, of The Ardent Somdomite.

Obregon Petrie possessed a maestro's touch with most of the district's repugnant, ever-recrudescent maladies, though his tinctures, creams, crystal amulets, cowpat exfoliants, vegetable poultices, infusions of sheep's urine, and like remedies provided little amelioration of the "waking dream" Land's End drifted through each day until nightfall.

Only one of Dr. Petrie's medicaments was known to relieve the diurnal somnolence and nocturnal abandon of his clientele. Alas, this balm came scarce and dear to the family exchequer, and was required for personal use by Dr. Petrie in such prodigious quantities that seldom could a drop be spared, even for those whose means might otherwise afford its purchase.

Since that long ago, mysterious collision of the Ardent with the archipelago of saber-toothed guano outcroppings beyond Zabriskie Harbor, the wags of neighboring Loch Stochenbaryl, East Clamcove, and Swill-upon-Mersey (communities themselves notorious for the maniacal swiving of bovine herds and poachery of game hens) cast withering execration upon our seaside enclave as "haunted."

Land's End's denizens indeed excited alarm with their sleep-starved, hallucinatory revels at eventide. Yet aside from its reversal of the customary ordering of time, Land's End was no better and no worse than other grubby, licentious coastal hamlets dependent for revenue upon hard-drinking, brawlsome, lecherous dockworkers and sailors crowding their domains.

By day, Land's End presented the chance traveller a dusty, unpeopled village, its serpentine lanes and ill-cobbled thoroughfares traversed by pariah dogs and an occasional disoriented porcupine or muskrat. At best, such a wayfarer might glimpse Dimitrios, the baker, who roused himself at cock's crow to knead and yeast the town's famous savory biscuits; Humbolt, the butcher, might be visible through a scrim of turdlike, mauve and scarlet sausages pendant in his grimy window, slamming a razor-honed cleaver into pork loins and accordionlike sides of beef; at Myshkin's Confectioners, a jewel box of delectable, fruit-pimpled cakes and fragrant pies piped their siren aroma long hours before the wild, thistled hills behind Loch Stochenbaryl engorged the dissolute afterglow of dusk.

But the veins of these night-sleeping merchants ran with foreign blood. Their ways were not the town's ways. They had suppurated from distant, oily realms, where barbarism waved its crude, intemperate sceptre. Immune to indigenous distress, their ruddy health seemed itself symptomatic of more furtive, hence more virulent inner riots of depravity.

Dimitrios was Greek, his ready smile unquestionably a pederastic leer; Humbolt, East Prussian to the core, disported all the gruff, militaristic vulgarity of his ilk; Myshkin, with his mincing feminate flourishes and constant stroking of his apron's forepart, belonged to some obscurantist Christian sect, or worse. His shanty, perched amid the phosphorescent lichen beds of Mica Slide, featured weeping icons and statuettes of apocryphal-sounding saints and starets, whom the few who'd ever ventured there presumed to be satanic fetishes and hoodoo simulacra of the townsfolk.

The ululating tongues of Gin Lane asserted that Myshkin's piety dissembled a cunning, avaricious Jew behind the confectioner's sugar with which he was usually festooned, that the dough of his cakes and eclairs was kneaded with the blood of Christian infants, and that his annual vacations were furtive trips to the Bilderberg Meetings, whose members rule the world sub rosa.

Such, at least, were the primitive, nugatory blatherings among the ignorant townsfolk. A few of us who lived at Land's End -not Those That Know, whose impenetrable secrecy concealed their very identities, but those of us, I mean to say, who knew Petrie-were acquainted with another side of the distinguished doctor, for Petrie's familiars regularly gathered in his rooms for evenings of bezique and the requisite blinis and caviar, washed down with flutes of French champagne, to which Petrie treated us when, almost every week, as he put it, his "ship came in ahead of schedule." What ship that was, the townspeople knew not; the Chinese coolies at the docks, however, who whiled their sparse hours' reprieve from herniating labor and the cruel lash of the harbormaster's bullwhip in Gin Lane's crapulous warrens of aromatic lassitude, knew Petrie's vessel well. But these prematurely wizened, cryptic Orientals kept their buccal orifices zipped for all but the insertion of the succoring pipe.

The motley of Petrie's acquaintances included Khartovski, a former Marxist-Leninist pamphlet-monger with a doctorate degree from the London School of Economics, which had done nothing to relieve his chronic penury. Khartovski's elongated, boneless form, its head resembling a speckled egg sprouting two taut braids of chin-length moustache, habitually draped itself athwart Petrie's green and beige striped sofa.

Sporadically, as if recalling in his cups the sylvan highlands and dales of an imaginary youth (Khartovski hailed, if that is the term, from a nameless Crimean obscurity), he declaimed Odes and Lays of the Robert Burns and Ettrick Shepherd variety in a guttural Russian accent.

Marco Dominguez, a Cameroonais of anthracite coloration, forever in demand for impromtu, unpaid repair work by Land's End's ennui-stricken grass widows, invariably joined us for bezique and regaled us with tales of bygone wildlife encounters and trophy maidenheads acquired in the bush. This nobly-hewn African émigré had amassed a fortune in small arms deals at the precocious age of twenty-two.

It was said that Marco could assemble a Kalashnikov from scattered parts in the time it takes a teakettle to raise a simmer. He dressed with a dash and flair rarely attempted in the rough-and-tumble sinkhole of our seaside purgatory, for lack of a kinder term. Marco, whose bearing suggested that of a tribal prince, wished to live the retiring life of an English gentleman from the Edwardian era, despite his much-sought, reputedly enormous dexterity and insatiable appetite for minor household repairs.

Another of Petrie's callers, Dr. Philidor Wellbutrin, was a rotund, excessively flatulent, puff-eyed OB/GYN (such, at least, was the euphemism active among the town's tarts and ostensibly virginal, unmarried daughters), whose ungovernable mane of flame red hair matched a ready tongue as fiery as his whorling tresses.

Petrie's salon further included Colecrupper, the local auto mechanic, an autodidact of vast pretentions and meager learning. These evening hands of bezique were further enlivened by visits from Thalidomido, a bow-legged, Umbrian dwarf, whose head followed the contour of a Bartlett pear, his torso that of a Bose stereo speaker. The soul of gaiety at Petrie's-save during cyclical spells of depressive rage that came upon him without warning-Thalidomido administered the local doll hospital, and reportedly terrorized its abject staff of "little people" with asperities and cutting personal remarks, alternating with melancholic, tearful vows to hurl himself from Strumpet Margot's Cliff, a crumbling extrusion of laterite on the edge of the lower town. Strumpet Margot had been driven to her end by a cavalry officer of wretched morals; the edge of the abyssal drop that bore her name was a favored setting for moonlight picnics and for carnal liaisons in motor vehicles whose owners Colecrupper derived tart, sanctimonious glee from identifying by their license plate numbers.

I do not suggest that I was Petrie's sole confidante, though because I rented a suite of rooms on his topmost floor, I "knew him" better than others. I did, in truth, pass greater time in Petrie's company than they, being young and, some said, comely as a rogue yet shy as a peacock hen, as I am afflicted with a speech disorder of a mortifying nature, and, as Petrie often teased, with a sigh of envy, "footloose and full of dreamy fancies." I was, in consequence, "more privy" (a locution I found particularly unfortunate, though the doctor intended a single entendre) to an occluded side of his existence.

With regard to many, though hardly all matters, the category of "confidante" would have encompassed much of Land's End and its periphery. Petrie could keep practically nothing to himself, even when discretion strongly recommended otherwise.

We card partners were hardly unaware that Petrie's "miracle remedy" for the town's primary ailment was clove-flavored tincture of laudanum, upon which Petrie himself had a punishingly copious dependence.

The realm of murk I alluded to just now, which Petrie kept truly secret, comprises much of my story here. He kept this realm sealed off from his other intimates and everyone for the excellent reason that his life depended on it-certain episodes of which, based entirely on the doctor's ipsissima verba, I record here, perhaps to no great purpose.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from THE SHANGHAI GESTURE by GARY INDIANA Copyright © 2009 by Gary Indiana. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.