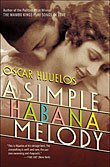

Excerpt from 'A Simple Habana Melody

|

|

|

| Chapter One

In the Spring of 1947, when Israel Levis, composer of that most famous of rumbas "Rosas Puras," returned to Habana, Cuba, from Europe aboard the SS Fortuna, those of his old friends who had not seen him in more than a decade were startled by his appearance. He was not yet sixty, but his hair had turned white and he had grown an unruly beard, so that he resembled a forlorn guajiro of the countryside, or the painter Matisse in his later years. Peering out at the world through the distortions of his thick-lensed wire-rim glasses, his eyes seemed lost, as if under water, and he was gaunt, perhaps too frail, his expression careworn, and, in any event, beyond easy recognition — a bit of a joke because during his heyday in the Habana of the 1920s and early 1930s he had been quite tall and broad-shouldered and so corpulent that while walking along the narrow sidewalks of Habana on his way to the music conservatory or to the Teátro Albisu he would have to stand aside, his back pressed flatly against a wall, or duck into a doorway, to allow the ladies with their parasoles and beaded purses to pass. So great was his girth and imposing physicality that with his trademark mustache he reminded his friends of the silent-film comedian Oliver Hardy, "El Gordo" (of "El Gordo y el Flaco," "The Fat One and the Skinny One"), which had become one of his affectionately intended nicknames, an appellation that he, in his good nature and with his grand reputation, frequenting the bars and restaurants and concert halls of the city, had always taken in stride. But by the time Israel Levis sailed past the Morro Castle and its lighthouse toward the rosified fortifications of La Punta and the glories of Habana proper, its blanched neoclassical facades as regal as Cartagena's, he had undergone certain transformations, for the events of his recent past had not been in keeping with the comforts and pleasures that his bourgois existence in Paris and fame as a composer and orchestra leader had accustomed him to. With his stooping shoulders and bent back, he seemed to have shrunk to half his original size, and he had lost so much weight during the war that he now floated through the voluminous expanses of his old linen suits. In fact, he, whose idea of a diet had been to forgo a second helping of crème brûlée or strawberry shortcake after a heavy five-course dinner in the Paris Ritz, was now as thin, if not thinner, than Stan Laurel, El Gordo's dim sidekick, and might have been called "El Flaco" had the clock been turned back to his glory days, and had the events of his recent years not seemed so tragic, or confounding to his soul. He had never been a handsome man, even in his best days; he did not have the Spanish good looks of his older brother, Fernando; rather, he considered that his charm had once arisen from his gallant manner, his affability and the attention he paid to others, staring directly into their eyes, save when he felt blinded — or outraged — by the most beautiful of women or the most strikingly handsome of men. In those moments a mixture of envy and admiration entered his heart, for these favored daughters and sons of life, moving through the world with effortless grandeur, embodied the very qualities of beauty that he had always aspired to through his music. Some women were like glorious sarabands, their dark and intense eyes mysterious as the deepest tones of an operatic aria; others more lustily disposed — the cheap women whom he had often cherished in his youth — were like jaunty rumbas, the wild gyrations of the Charleston. And men? Some were as graceful as the tango, or surefooted and capricious in their movement through life as the habanera — while he, lumbrous, awkward and ever careful, had always been the equivalent of a waltz or a simple box step. For many years he knew this to be the truth, as most of his grace lingered within, and he had spent so many hours, as a younger man, in private self-ostracism, wishing he could change this or that on his face or some part of his body, as if it were not enough to attract others through the power of his understated personality and a presence that most found enchanting; how foolish he had been, he now thought, to have wasted so much of his time on such petty concerns. He left the port city of Vigo in northwestern Spain a week before, the ship stopping off for one morning in the Canary Islands to pick up other passengers. He brought along a single black trunk containing what personal effects he had managed to salvage from his last years in Paris during the German occupation: letters that he treasured — among them his correspondences with Stravinsky and Ravel; a dense cache of notes from his old composer poser friends in Habana, Ernesto Lecuona and Gonzalo Roig to name but two; and of course those correspondences with his own family in the cities of Habana and Santiago, letters whose nostalgic significance and worth increased as he entered into his period of troubles. It should be mentioned that among the treasures he managed to smuggle away with sympathetic friends, among them the kindly but inept Spanish attaché Señor Ramos, were the letters and postcards he'd received over the years from one Rita Valladares, of Habana, with whom he supposed he'd once been in love — or as close to love as so guarded a man could have been. He would sigh thinking about Valladares, the petite singer affectionately known to many as "La Chiquita" — my beloved — and over how so many years had passed without his ever once saying how deeply he felt about her. Even when he belatedly realized just how much he loved... (Continues...)

|

|