A year has passed since LA County returned a strand of Manhattan Beach waterfront property to the descendants of the Bruce family. Known as Bruce’s Beach, the land was taken from the family nearly 100 years ago through eminent domain.

Now Santa Monica faces a similar issue. Last week, the City Council voted to explore compensating the descendants of a Black man named Silas White for his plot of land on Ocean Avenue near Pico Boulevard. Decades ago, White dreamed of converting a building he owned into the Ebony Beach Club, a place where African Americans could feel safe from discrimination while at the beach in Santa Monica. The city took the land, saying they needed it for public parking. Now the luxury Viceroy Hotel sits on the site.

Silas White was an entrepreneur who moved to Santa Monica in the 1920s, and he started the Ebony Beach Club (with a white business partner) on a property he bought in the 1950s, explains Alison Rose Jefferson, historian and author of Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era.

“He saw it as a place for elite African American leisure. And one of the first people that signed up for the club was the famed singer, Nat King Cole. And with that, he envisioned that they would have this place to meet for socializing … where they could change their clothes [as they were] going to the beach. They would organize various kinds of social trips revolving around California coastal outdoor activities, such as ocean fishing trips,” she says.

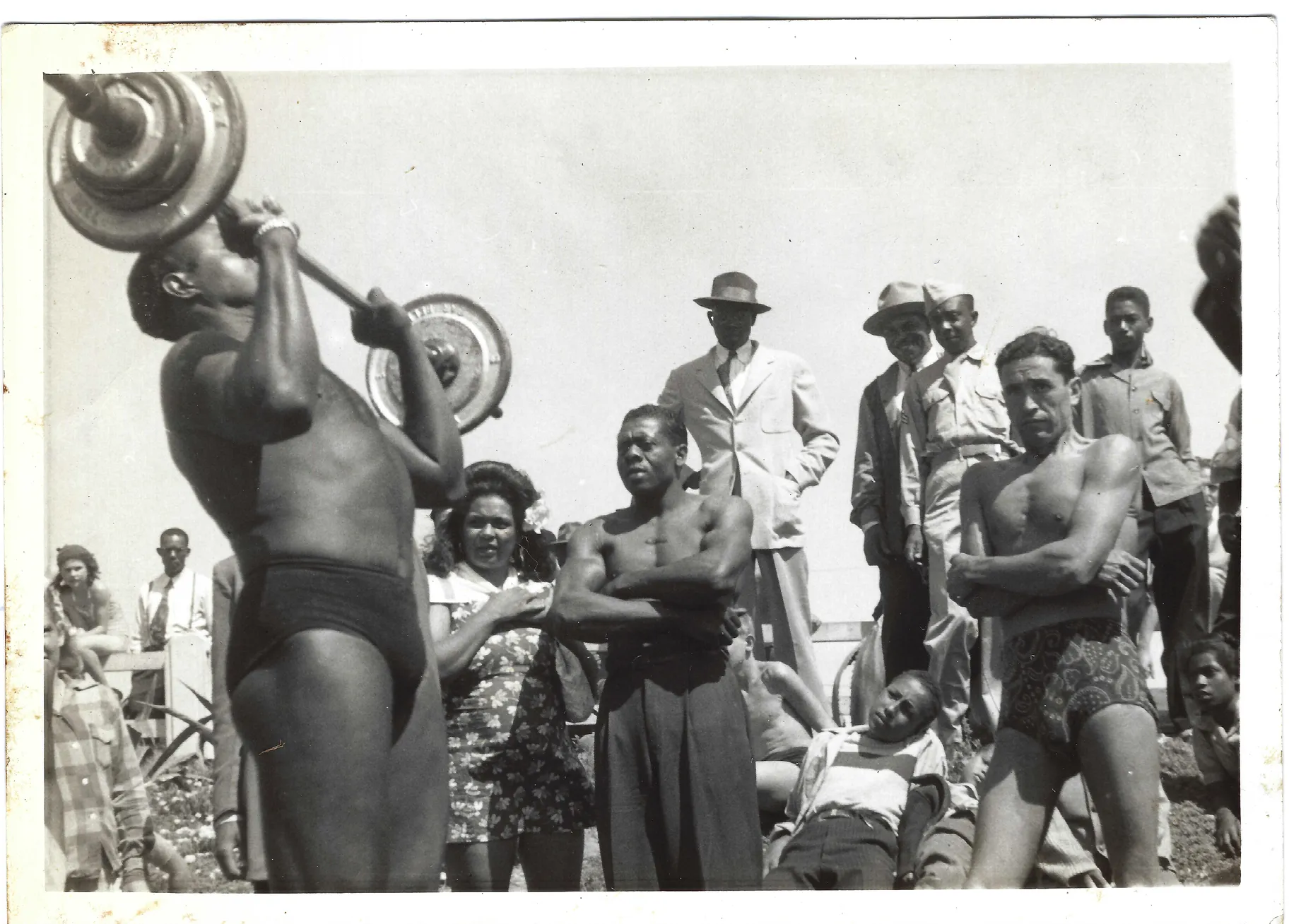

John “Johnnie” Rucker participated in the Black bodybuilding culture of the era, 1945–50, in Santa Monica. Courtesy of Konrad Rucker.

Jefferson notes that Santa Monica was always home to an African American community, and their initial stage of setting up residency looks different from today’s development.

“This was the edge of Ocean Park at that point in time … where Silas White was trying to build his beach club … where some other businesses attempted to establish themselves around beach culture that were pushed out due to racism of Santa Monica's white business class.”

Jefferson emphasizes that Bruce family’s settlement (in Manhattan Beach) was instrumental in enabling the White family to pursue restitution of their land loss in Santa Monica.

“They're getting recognition, both Bruce's Beach and the Ebony Beach Club, on a broader level because there's money involved in it. … We've been working on commemoration of the sites … and honoring the people who fought for and struggled for their civil rights and for California freedoms in terms of enjoying outdoor space.”

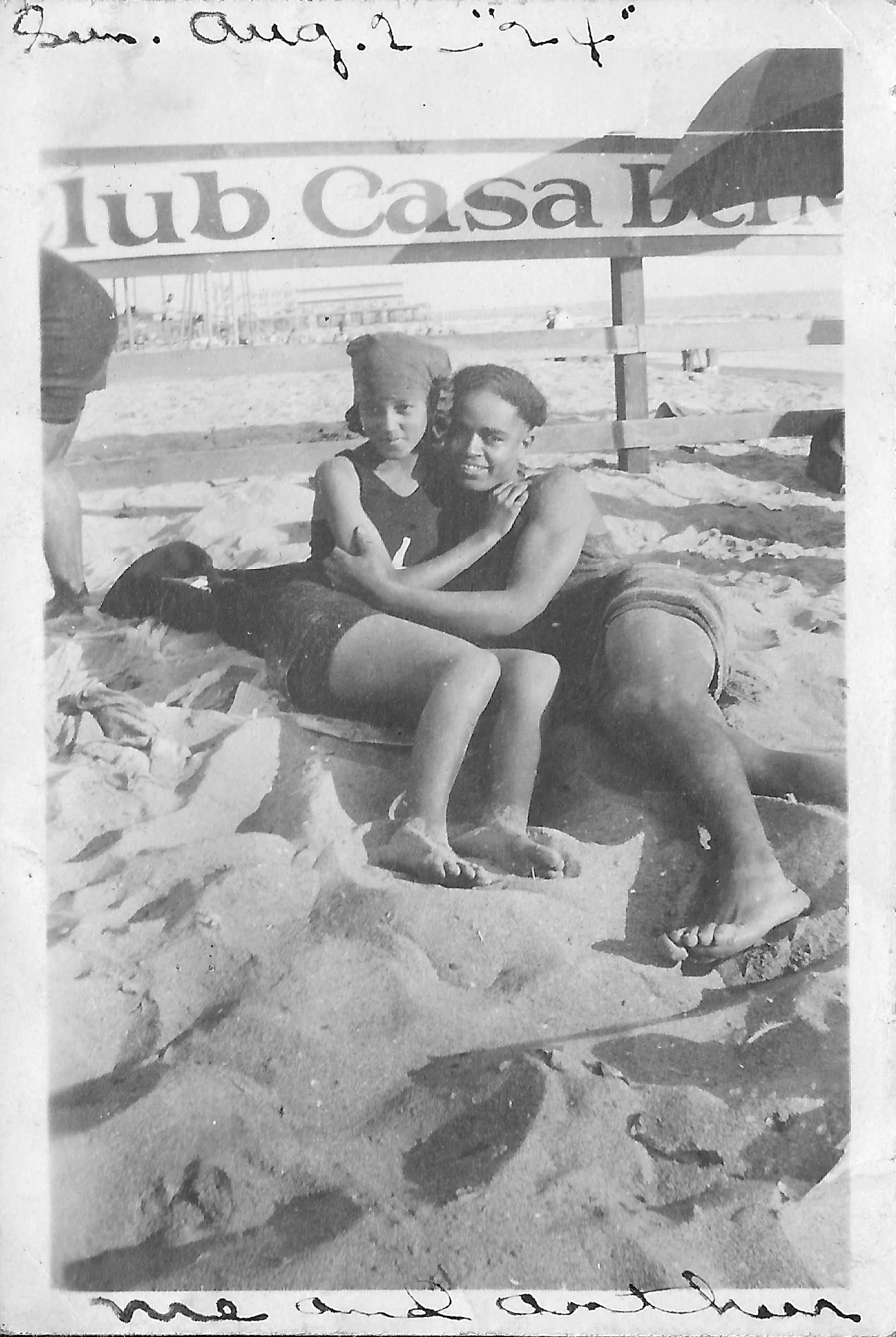

Verna Deckard Lewis (later Williams) and Arthur Lewis sit in front of the Casa del Mar beach club fence, Santa Monica, August 2, 1924. Credit: Verna Deckard L. Williams Collection; courtesy of Arthur and Elizabeth Lewis.

Now the council plans to have city staff research the situation, Jefferson says: “They have pulled up a few newspaper articles that they found on the 1950s dispossession. And so they have city records that they potentially could go back and find. And then they will come up with … what they think might be appropriate in terms of some compensation to the white family.”